Unless India conserves water, its food and energy security will be threatened in the near future

Even as we talk of ensuring food security, the competition for limited water and energy resources has become worse due to the unpredictable weather. For farmers in India, the shocks just don’t seem to end. Several States have faced two successive droughts while 13 districts of Bundelkhand have suffered three. The droughts were followed by unseasonal hailstorms and rainfall, which destroyed crops across the kharif and rabi seasons.

In the national capital, it has been an uncharacterically warm winter. Daytime temperatures have been the highest in 20 years. The story across several northern States is similar with warmer winters in Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Leh in Jammu & Kashmir, Rajasthan, Haryana and Punjab.

This pattern has consequences: Weather behaviour has implications for water resources, which in turn has implications for energy production and food security and the economy. This is why both the Reserve Bank of India and the village farmer waits with bated breath for monsoon predictions. Even in a scenario where the weather behaves as expected, India has to deal with a huge gap between demand and supply of water. One estimate indicates that by 2050 the demand-supply gap will touch 50 per cent. How will the thirst be quenched, food be produced and industries survive?

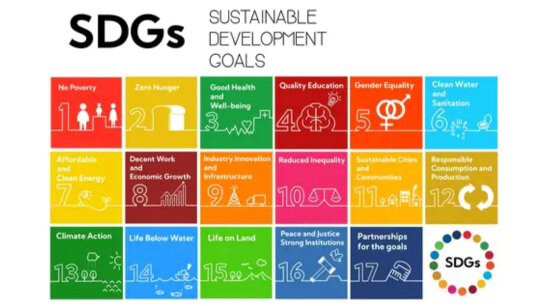

According to the UN, food output must grow by 60 per cent to feed a population of nine billion or more in 2050. Already around 800 million people go to bed hungry. This hunger is unacceptable and, worse still, avoidable. Yet, global hunger is only expected to get worse.

Water and energy are inter-dependent. Water is required for energy production and energy for extraction, collection, storage, treatment, purification, transportation and distribution of water. More than 70 per cent of industrial water-use in India is for energy generation.

Agriculture and food production require critical inputs of water and energy. Agriculture already accounts for around 70 per cent of global freshwater withdrawals; and irrigation requirements are expected to grow by another six per cent by 2050. But, by 2030, the world will have to confront a water supply shortage of 40 per cent.

Globally, the food sector accounts for around 30 per cent of the world’s total end-use energy consumption, more than 70 per cent of which is used beyond the farmgate. But more than 1.3 billion people (19 per cent of the global population) still lack access to electricity, and roughly 2.6 billion use solid fuels (mainly biomass) for cooking.

India currently feeds 1.2 billion people, (17 per cent of the worlds’ population), using less than three per cent of the world’s arable land and less than four per cent of the world’s freshwater. Around 80 per cent of water use is India is for food production, some 60 per cent of which is groundwater. About 19 per cent of the total electricity and 12 per cent of total diesel consumption is used for irrigation and post-harvesting processes.

India has vast amounts of water but it may soon become a water-stressed state. India continues to be the largest groundwater extractor in the world. Decades of neglect and misuse have squandered away this resource. A database of India’s water assets does not exist and estimates vary widely. In such uncertainty, how can one gauge the situation?

Biological, organic and inorganic pollutants contaminate almost 70 per cent of surface water resources and a growing percentage of groundwater reserves. As many as 19 States face groundwater contamination. Groundwater in over 200 districts is polluted. Only 21 per cent of the municipal sewage is treated. The remaining is disposed untreated into waterbodies, resulting in pollution of rivers. A business as usual approach towards this problem will only accelerate the pace at which we are hurtling towards a parched and poisoned future.

India first needs to acknowledge that there is a problem which needs to be addressed on priority. We need to build consensus on the utilisable water. While it is true that agriculture gets the largest share, conservation across all users is important. In fact, water needs to be conserved wherever possible. For example, diverting rain water from flooded fields and unexpected rains can help save crops.

At the farmer’s level, a significant amount of energy is used to pump and distribute water for irrigation. This energy footprint can be reduced by employing measures that conserve energy. In fact, a lot more needs to be done to scale up renewable energy use in the agricultural sector.

Agriculture modelling and forecasting needs to improve, and shared with the cultivators. Modelling needs to factor in water and energy requirements. At the local level, villagers plan their sowing based on water budgeting. Such practises must spread.

Over the past few decades, agricultural innovation has taken a back seat. Agricultural institutes need to be revived. The much-talked about second green revolution needs to deliver. There are no fool proof measures to deal with the weather but these efforts can help alleviate the crises.

(The writer is Policy Lead: Food Security, Resource Scarcity and Climate Change with IPE Global)