Drought-hit residents are starving to death or committing suicide. But a turnaround can be scripted for them

Bundelkhand, a region that sprawls across 13 districts in the States of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, is falling apart. Three successive droughts, unseasonal rains, and thick-skinned Governments have wrecked the ecology and economy of the region. With reports highlighting suicides, migration, hunger and starvation, the question is: Can the wheels of fortune change in Bundelkhand?

Let’s start with drought: A multi-dimensional phenomenon, it is categorised as meteorological, hydrological or agricultural, depending upon its stage —whether it was just rainfall deficit or had an impact on the hydrological cycle and agro-ecosystems. A drought affecting food security and livelihood support systems beyond the level of community resilience is a categorised as a disaster. For Bundelkhand, 2015 was the third consecutive year of drought. The rabi crop was damaged by hail storms; unprecedented rains in February-April followed by drought during the kharif season, left the agricultural economy in shambles.

The Bundelkhand districts in Madhya Pradesh are facing an acute water shortage, with Government surveys indicating that more than 50 per cent of water sources have dried up. This figure is expected to rise in the coming months, generating water crises of huge proportions. Women are the primary victims of this crisis, spending a significant proportion of time travelling great distances to collect drinking water. Migration has increased to 60-65 per cent as compared to 30-40 per cent in a normal year. Food crisis has reached alarming levels too with a whopping 25 per cent of the community malnourished. Cattle is being abandoned for lack of fodder while compensation from the State leaves much to be desired.

The Bundelkhand districts in Uttar Pradesh are doing no better. A survey conducted in 2015 by Swaraj Abhiyan and Parmarth across 100 plus villages in all Blocks of the seven UP Bundelkhand districts indicated large scale damage for urad, til, soyabean, bajra, jowar, moong and arhar crops. Struggles for drinking water have increased, as evident from the drying of hand pumps and deteriorating water quality. This is in sharp contrast to Union Government data which claims, for example, that 2,364 of the 2,450 habitations in Budelkhand’s Banda district in Uttar Pradesh receive drinking water supply of 50 litres per capita per day. Similarly, the official figures for Chitrakoot district claim that 1,930 of the 2,128 habitations are full covered.

With regard to food intake, a disturbing 19 per cent of those surveyed were found to be going hungry at least once in the last 30 days before the survey. Vegetables and pulses had all but disappeared from the dining table. Residents were borrowing food, eating grass rotis and drinking grass juice; many had to ask for loans, others took their children out of school.

So, is it even possible to script a turnaround? The answer is a resounding yes. Historically, Bundelkhand was thickly forested but is now a bare hilly terrain with sparse vegetation. Bundelkhand has all but lost its forest cover. Thirsting for water, the region is drained by several rivers of the Yamuna river system including the Yamuna, Ken, Betwa, Pahuj and their tributaries. The region is also known for its Bundela and Chandela tanks and wells.

Agriculture in Bundelkhand is rainfed and diverse but also under-invested, risky and vulnerable. Extreme weather conditions add to the uncertainties. The scarcity of water in the semi-arid region, with poor soil and low productivity, aggravates the problem of food security.

The healing of the land, the soil, the social fabric and the ecology will take time but long-term steps can also be used to address immediate requirements. For example, it is important to raise awareness about the realities of ground zero. However, one need not paint a dismal and hopeless picture, instead, one should focus on solutions.

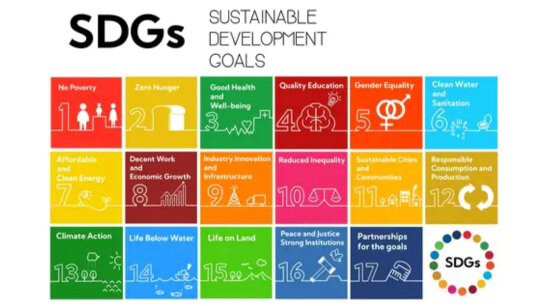

Stakeholders should get together to make Government programmes work. Several Government programmes such as the mid-day meal scheme and the rural employment guarantee scheme can be availed of. Civil society must begin healing the land. It can start by identifying programmes that can address soil and water concerns and implement these effectively. Agricultural scientists should also be involved to identify crop varieties suited for the region. They must work with the farmers to promote and cultivate crops.

Additionally, institutions such as the Indian Grasslands and Fodder Research Institute should step in to develop and promote climate resilient fodder and grass crops that can meet the needs of the livestock. More grain banks, seed banks and fodder banks should be set up. The medical fraternity should be involved to address public health issues. Equitable drinking water supply needs to be arranged under community management.

All this requires money. Villages need to be adopted and turned around. Funds from Government sources, institutional donors and corporate social responsibility initiatives must be made available and accessible. Even Local kirana shops can chip in at the grain banks. Let those who took their own lives in desperation and the suffering of the living dead not go in vain. Bundelkhand needs our support for its redevelopment, rebuilding and resilience.

(The writer is Policy Lead: Food Security, Resource Scarcity and Climate Change with IPE Global).