Want economic growth? Just feed 50 per cent of India’s population right, writes INDIRA KHURANA

The year 2015 ended with several reports on women and gender. Though none of them addressed the issue directly, the findings send a strong message: Let’s feed our women right. According to the McKinsey Global Institute report: The power of parity Advancing Women’s Equality in India, the country could boost its GDP by $0.7 trillion in 2025 or 16 per cent of the business-as-usual level, which translates into 1.4 per cent per year of incremental GDP growth for India. A whopping 70 percent of this increase comes from raising India’s female labour-force participation rate from 31 per cent at present to 41 percent in 2025, to bring 68 million more women into the economy over this period.

But to realise this, gender gaps need to be addressed. The question to also ask is: Are these women healthy enough? The report on Gender Inequality Index revealed that India continues to rub shoulders with others at the bottom of the ladder, faring a dismal and alarming 127 on the gender inequality index. This index is based on the parameters of reproductive health, measured by maternal mortality ratio and adolescent birth rates; empowerment, measured by proportion of parliamentary seats occupied by females and proportion of adult females and males aged 25 years and older with at least some secondary education; and economic status, expressed as labour market participation and measured by labour force participation rate of female and male populations aged 15 years and older.

India also ranks 141st out of 142 nations and 2,062 districts in the world that are categorised as gender critical when it comes to health and survival of women as compared to men. In these cases also, the nutrition links were not highlighted.

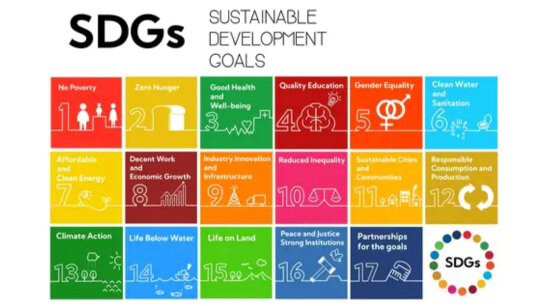

Malnutrition is a severe social problem for any country and affects productivity in many ways. The problem of malnutrition is especially critical in case of women and children. Despite India’s 50 per cent increase in GDP since 1991, more than one third of the world’s malnourished children live in India.With the highest burden of undernutrition — one in every three children below the age of three is underweight Indian data plays a large role in shaping global statistics, given that around 40 per cent of the world’s stunted children under the age of five and nearly 50 per cent of the wasted children are from here. Eradication of poverty and hunger must be a priority area of development, in policy, programme and practice.

Women have a crucial role to play in defeating hunger and ironically they are often victims of hunger. Prolonged crises undermine food security and nutrition, and when a crisis hits, women are usually the first to sacrifice their food consumption, so that their families can eat.

Gender inequality thus exists in another critical area: Food and nutrition security. Factors responsible for this range from sheer poverty to access to natural resources and a cultural system that believes that women must eat what remains after the lord and master has taken his fill and so have the children. A women’s nutritional status has important implications for her health as well that of her children because a malnourished woman is very likely to give birth to a malnourished child, vulnerable to disease and infection. Underweight babies are 20 per cent more likely to die before the age of five.

Adequate nutrition is critical to a child’s development: Under-nutrition not only retards a child’s growth but also affects its future productivity and capabilities. Nutrition-deficient individuals are less productive at work. Low productivity results in low pay trapping them in a vicious circle of under-nutrition.

Ample proof exists of how women have coped with hunger for themselves and their family. The resulting loss of dignity is all unnecessary and totally avoidable. Nothing can be more poignant than a woman who has to take care of her family after a disaster. For example, drought-related migration results in the women being left behind and having to cope with addressing the needs of the other members of the family. Farmer suicides have left the women coping all by themselves. With no agricultural produce to rely on and little support from the state, the desperate times call for desperate measures. No wonder then that women in rural Bundelkhand villages are resorting to using grass to make rotis. While others sell their starved bodies for a pittance. Women must have access to natural resources. Yields of women farmers are between 20 per cent and 30 per cent less, simply because they do not less access to inputs such as improved seeds, fertilisers and equipment. Giving them access to these inputs would also result in bringing down the hunger numbers by 100 to 150 million.

India’s women engage much more in unpaid work than men: These wonder women do almost 10 times the amount of unpaid care work that men do. Three-quarters of unpaid work is routine household chores exacerbated by poor access to basic services such as sanitation and clean sources of cooking fuel. There unpaid work burden can be reduced by providing access to clean fuel , safe drinking water close by and access to sanitation.