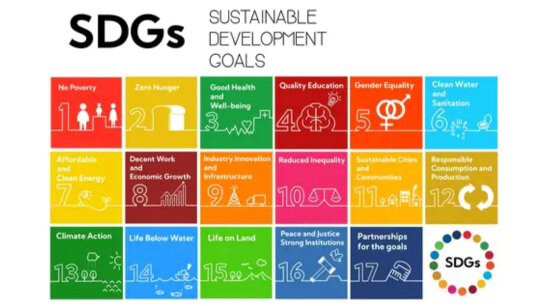

The current development agenda is driven by five transformative shifts: to leave no one behind; to put sustainable development at the core; to transform economies for jobs and inclusive growth; to build effective, open and accountable institutions for all; to forge a new global partnership. The 17 specific goals with 169 targets recently adopted by UN member countries bind the nations together under the universal framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). According to the African Development Board (AfDB), the transformative vision of the SDGs is to meet the dual challenge of overcoming poverty and protecting the planet, which requires an estimated USD 7 trillion per year globally out of which around USD 34 trillion per year will be required for developing countries only to meet basic infrastructure, food security, climate change mitigation and adaptation, health, and education. Economists across the world advocate that with such large financial implications, the world, especially the developing part, must find ways to raise funds in addition to the available aid. While the debate continues on the financial commitment by the developed countries through official development aid (ODA) to meet SDG targets, it is recognized that domestic resource mobilization (DRM) will play an important role in achieving the upcoming goals. Several studies point out that reliance on internal resources through DRM rather than aid ensures better accountability of public policy towards citizens. It is estimated that every additional money raised through domestic taxation reduces external debt liability up to an equivalent amount, thereby helping to constrain the growth of debt to sustainable levels (Culpeper and Kappagoda, 2007: 16). In the face of these considerations, DRM is inevitable in developing countries. Most African countries, like India, are at a critical juncture in their development and steps towards reducing dependency on foreign aid needs to be taken in parallel to increasing public investment in development initiatives. India has been successful in mobilizing domestic resources mostly after the economic liberalization that began in 1991. India’s dependence on the net ODA has dropped from one percent in 1991 to 0.13 percent in 2013, (World Bank 2014). The gradual turnaround in India’s economic situation provides great learnings to Africa, which is experiencing conditions similar to India’s during the 2000s.

Some critical steps that African countries must take to enhance DRM are in theareas of 1) policies through tax reforms, savings and probusiness reforms, 2)administrative prudence including measures like capacity building and institutionalstrengthening and 3) effective implementation supported by the private sector, civilsociety organisations (CSOs) and regulatory and monitoring bodies.The Indian story in improving domestic savings can prove instrumental in fuellingAfrica’s overall economic growth and poverty alleviation. In India, the biggest sourceof savings is the household sector, followed by the private sector and the publicsector. The selfhelp group (SHG) model, which promotes thrift and credit, financialliteracy and financial inclusion amongst women living in poor communities whootherwise do not have access to savings, provides an opportunity to also enhancethe share of household savings. Recently, under the Knowledge PartnershipProgramme, IPE Global facilitated the development of an action plan to adopt aSHG based empowerment programme, called Kudumbashree, in two regions ofEthiopia.Taxes are an important domestic resource and have a role to play that is distinctand complementary to the role of private savings. Most importantly, taxes and othergovernment revenues should fund the provision of essential public goods such aseducation and health services, infrastructure development and maintenance, lawand order, and efficient public administration.In India, tax reforms involving lowering of tax rates, broadening the tax base andreducing loopholes have been undertaken and have been successful in raising thetax ratio in the case of personal and corporate taxation. Most African countriescollect only a fraction of potentially available taxes. While some countries such asBotswana have a high tax revenue to GDP ratio (27 percent in 2012), there aremany others whose performance is closer to Chad’s four percent of GDP. Hence,the efficiency and effectiveness of the system can be considerably improved inmany countries through policy innovations. Instruments like technology transfer andknowledge sharing in areas of tax reforms provide the developing countries withopportunities to engage with each other in addressing domestic issues related torevenue generation.For the post2015 agenda, the key building blocks of governance are fiscalaccountability and transparency. For both, India and Africa, to be able to

successfully manage their own resources to their best interest, there is a need toprovide a mechanism to guide against mismanagement and misallocation of scarceresources. At the same time, in the drive for good governance, in order to promotetransparency and reduce corruption, CSOs can play an important role in planning,monitoring and evaluation processes in India and Africa. The CSOs can contributeto SDGbased poverty reduction strategies in at least four ways: publicly advocatingfor pressing development concerns, helping design strategies to meet each target,working with governments to implement scaledup investment programmes, andmonitoring and evaluating efforts to achieve the Goals. Under the aegis of SouthSouth cooperation, both regions can benefit by sharing experiences and helpingeach other in achieving common goals.(24.10.2015 In arrangement with KPPIPE Global, an international developmentconsulting group, of which Ashwajit Singh is the managing director. The viewsexpressed are those of KPPIPE Global. He can be reached atasingh@ipeglobal.com)